For companies trying to win corporate and consumer adoption of their own NLP technologies, this is a long-awaited moment. And one of the firms that thinks 2012 could be the year this market really takes off is VirtuOz VirtuOz, Inc., a Paris-born company that moved its headquarters to Emeryville, CA, in 2009. First IBM’s Watson beat Jeopardy champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. Then Apple captivated mobile consumers with the iPhone 4S, which included an enhanced version of Siri, the voice-driven assistant born at Menlo Park, CA-based SRI International. Suddenly, the idea that computers might be just as good as humans at carrying out certain types of requests seemed a lot less far-fetched.

First IBM’s Watson beat Jeopardy champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. Then Apple captivated mobile consumers with the iPhone 4S, which included an enhanced version of Siri, the voice-driven assistant born at Menlo Park, CA-based SRI International. Suddenly, the idea that computers might be just as good as humans at carrying out certain types of requests seemed a lot less far-fetched.

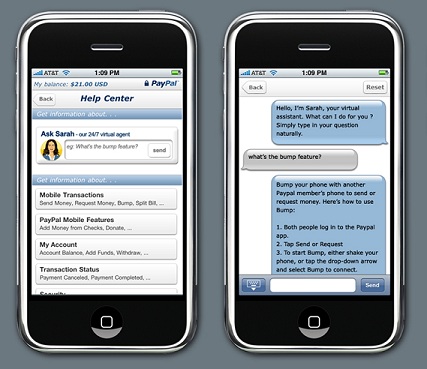

Fresh off a $7 million extension of its Series B funding round last June, VirtuOz wants to conquer the worlds of online marketing, sales, and support with its virtual agents—personal question-answering systems designed to help customers get the information they want faster. The company has already picked up a few big clients. If you go to Symantec’s support pages, for example, you’ll meet Nathan, an expert on installing and troubleshooting the company’s antivirus products. AT&T has Charlie, PayPal has Sarah, video game rental site Gamefly has Ryan, and Michelin has—well, the Michelin Man. All are powered by VirtuOz.

CEO Steve Adams says his aim is to double the company’s client base in 2012. That’s a plausible goal, if research firm Gartner is correct in its prediction that 15 percent of the Fortune 1000 will be using virtual agents on their websites within the next three years. “We think we can get the lion’s share of that business,” Adams says.

VirtuOz is the brainchild of Ecole Polytechnique graduate Alexandre Lebrun and co-founders Callixte Cauchois and Laurent Landowski. Back in the mid-2000s, Lebrun believed that the day was fast approaching when computers would be able to understand humans simply from their speech or writing. “Alex would tell you that the ultimate evolution of the technology is going to be the personal virtual assistant who drives both our business lives and our personal lives,” says Adams. But as a near-term commercial application, Lebrun decided to focus on a more limited idea, the virtual agent—a system that sits within a company’s website and represent its brand in real-time communications with consumers.

In its simplest form, a virtual agent isn’t much more than a fancy search engine that can parse natural-language queries and find preformulated answers, the way the original Ask Jeeves did. But Lebrun and his cofounders wanted to go a couple of steps farther. First, they thought a virtual agent should be able to detect and respond to a user’s actual intent. If an auction site visitor types “I want to cancel my bid,” for example, they thought the agent should be able to deduce that they’re talking about a specific bid in an active auction, and show them what to do. That meant designing virtual agent software that could be tied deeply into a company’s knowledge bases and website functions.

Second, Lebrun and his co-founders wanted interactions with their agents to feel like conversations, with a personality at the other end who can recognize tone and mood and ask clarifying questions. That’s why VirtuOz gives most of its agents names and faces. Sometimes they’re photos of models, as with Symantec’s Nathan (see upper right), but usually they’re cartoon renditions. If this brings to mind images of Microsoft’s infamous Bob and Clippy, forget that comparison—VirtuOz’s characters are much less nosey.

For the first four years of its life, VirtuOz focused on the French, German, and U.K. markets. Travel companies and wireless carriers showed the most interest. In 2009, the startup moved its headquarters to the Bay Area in order to tap the local pool of engineering talent and go after the larger North American market. That’s also when the company raised $11.4 million in Series B funding, with Menlo Park, CA-based Mohr Davidow Ventures in the lead, and gave the CEO job to Adams, who’d previously led another MDV portfolio company called Sabrix. Today about a third of the VirtuOz’s 70 employees work from Emeryville.

The company’s virtual agents are simultaneously versatile and limited. If you go to VirtuOz’s own site, an agent named Chloe (after Adams’ third daughter, not the spy-tech whiz on 24) can answer your questions about the company’s history or the cost and features of the virtual agent technology. But she doesn’t know much about the world outside the company—even how VirtuOz’s software is different from that of competitors Next IT, noHold, or Creative Virtual, for example. If there’s a question she can’t figure out, she’ll direct you to a support form or a toll-free number. But overall, VirtuOz’s agents are a long way from passing the Turing Test: you won’t be tempted to wonder whether there’s a real person on the other side of the screen.

PayPal’s VirtuOz virtual agent Sarah on the iPhone

But that’s not really the point. The point is that interacting with VirtuOz’s virtual agent is more rewarding than sifting through a community support forum or FAQ document—and a lot more fun than waiting on hold to speak with a human.

VirtuOz prices its service based on the number of customer conversations a client expects its agents will handle each month. The bottom-line argument for virtual agent software, of course, is that it’s more economical than hiring real people to staff call centers or chat systems. But Adams warns that companies shouldn’t think of a virtual agent as a way to avoid having to talk to customers. “It’s one-tenth the cost of any human-assisted channel, but there’s a balancing act between lowering costs and keeping the quality of the user experience high,” he says.

A good customer experience, even if it’s with a virtual assistant, can leave a positive impression that benefits a company later, Adams says. In fact, he says VirtuOz’s most enlightened clients think of their virtual agents as part of their branding—and are paying for them in part out of their marketing budgets. “It’s actually a shift from customer avoidance to customer engagement,” he says.

Adams says the advent of Watson and Siri have made VirtuOz’s sales pitch a lot simpler. Executives nod when he explains that VirtuOz is basically Siri for enterprises. “It’s less about the cleverness and the sassy attitude and more about the things that really sit behind Siri,” he says. “One is natural language search. Siri is getting you to the one right answer. We have been doing that for a while, but now when consumers go to a company website they are going to want the same experience.”

Adams also points to Siri’s heavy use of context and personalization. Before answering a question, Siri frequently checks on a user’s current location or dips into their address book or calendar. In the same way, a virtual agent should not only recognize a customer, but understand what transactions they have underway and be able to jump in with helpful suggestions, Adams says.

After all, why shouldn’t a customer support site be at least as smart as your phone? “We’ve already seen the consumerization of IT, as people bring their devices to work,” says Adams. “Now we’re going to see the consumerization of the enterprise in the way it interacts with customers.”

Wade Roush is Xconomy’s chief correspondent and editor of Xconomy San Francisco. You can e-mail him at .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address) or follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/wroush